Turning your kitchen table into a Mad Scientist Laboratory!

Chemistry is an exciting subject for kids of any age, especially if you set up a natural discovery environment for them to safely explore in. Let’s find out how to do this with your own homeschool science learning environment.

At a university, one of the first things you will learn about in your chemistry class is the difference between physical and chemical changes. An example of a physical change happens when you change the shape of an object, like wadding up a piece of paper. If you light the paper wad on fire, you now have a chemical change. You are rearranging the atoms that used to be the molecules that made up the paper into other molecules, such as carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ash, and so forth.

How can you tell the difference between physical and chemical changes? There’s an easy way to tell if you have a chemical change: if something changes color, gives off light (like the light sticks used around Halloween), heat is absorbed (gets cold) or produces heat (gets warm). Some quick examples of physical changes include tearing cloth, rolling dough, stretching rubber bands, eating a banana, or blowing bubbles.

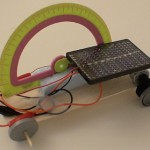

Let’s mix up chemicals that bubble, ooze, freeze, and change colors. Before we start, you’ll need to get these items together: a muffin cup baking tray, water, vinegar (acetic acid), baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), washing soda (sodium carbonate), rubbing alcohol, hydrogen peroxide, citric acid, ammonium chloride (don’t activate the cold pack, but instead cut open and empty the contents into a plastic bag and discard the water pouch inside), aluminum sulfate (“alum” in the spice section of the grocery store or drug store), a head of red cabbage and a clear liquid dish soap such as Ivory.

Cover your kitchen table with a plastic tablecloth (if you have small kids, put another tablecloth on the floor to catch the spills). Place your chemicals on the table. A set of muffin cups make for an excellent chemistry experiment lab. (Alternatively, you can use empty plastic ice cube trays.) You will mix in these cups. Leave enough space in the cups for your chemicals to mix and bubble up – don’t fill them all the way when you do your experiments!

Shopping List:

• Rubbing alcohol (largest bottle)

• Hydrogen peroxide (largest bottle)

• Baking soda (largest box you can find)

• Distilled white vinegar (largest size)

• Washing soda (near the laundry soap)

• Citric acid (optional, but nice to have)

• One head of red cabbage

• Clear ivory dish soap (small bottle)

• Alum (check the spice section)

• Single-use cold pack ( not the gel kind)

• Plastic zipper bags and old water bottles

• Muffin cup baking tray (12 cups or more)

Set out your liquid chemicals in easy-to-pour containers , such as water bottles (be sure to label them, as they all will look the same): alcohol, hydrogen peroxide, water, acetic acid, and dish soap (mixed with water). Set out small bowls (or zipper bags if you’re doing this with a crowd) of the powders with “scoopers” made of the tops of your water bottles. The small “scoopers” regulate the amounts you need for a muffin-sized reaction. Label the powders, as they all look the same.

Although these chemicals are not harmful to your skin, they can cause your skin to dry out and itch. Wear gloves (latex or similar) and eye protection (safety goggles), and if you’re not sure about an experiment or chemical, just don’t do it. (Skip the peroxide and cold pack if you have small kids.)

What about the red cabbage? Red cabbage juice has anthocyanin, which makes it an excellent indicator for these experiments. Anthocyanin is what gives leaves, stems, fruits, and flowers their colors. Did you know that certain flowers like hydrangeas turn blue in acidic soil and turn pink when transplanted to a basic soil? This next step of the experiment will help you understand why. You’ll need to get the anthocyanin out of the cabbage and into a more useful form, as a liquid “indicator”.

Prepare the indicator by coarsely chopping the head of red cabbage and boiling the pieces for five minutes on the stove in a pot full of water. Carefully strain out all the pieces (use a fine mesh strainer) and the reserved liquid is your indicator (it should be purple).

When you add this indicator to different substances, you will see a color range: hot pink, tangerine orange, sunshine yellow, emerald green, ocean blue, velvet purple, and everything in between. Test out the indicator by adding drops of cabbage juice to something acidic, such as lemon juice and see how different the color is when you add indicator to a base, like baking soda mixed with water.

Have your indicator in a bottle by itself. Old soy sauce bottles or other bottles with a built-in regulator that keeps the pouring to a drip is perfect. You can also use a bowl with a bulb syringe, but cross-contamination is a problem. Or not – depending if you want kids to see the effects of cross-contamination during their experiments. (The indicator bowl will continually turn different colors throughout the experiment.)

Your mission: To find the reactions that generate the most heat (exothermic), absorb the most heat (endothermic), and which are the most impressive in their reaction (the ohhhh-ahhhhh factor).

The Experiment: Start mixing it up! When I personally teach this class, let them have at all the chemicals at once (even the indicator), and of course, this leads to a chaotic mix of everything. When the chaos settles down, and they start asking good questions, I reveal a second batch of chemicals they can use. (I have two identical sets of chemicals, knowing that the first set will get used up very quickly.)

Tip for Testing Chemical Reactions: Periodically hold your hand under the muffin cups to test the temperature.

After the initial burst of enthusiasm , your science students will intrinsically start asking better questions. They will want to know why their green goo is creeping onto the floor while someone else just bubbled up hot pink, seemingly mixed from the same stuff. Give them the change to figure out a more systematic approach, and ask if they need help before you jump in to assist. Use the indicator both before and after you mix up chemicals, and you will be surprised and dazzled by the results!